The Man Behind Nosferatu. Plus: Skinamarink and a Pug in a Snowman Costume

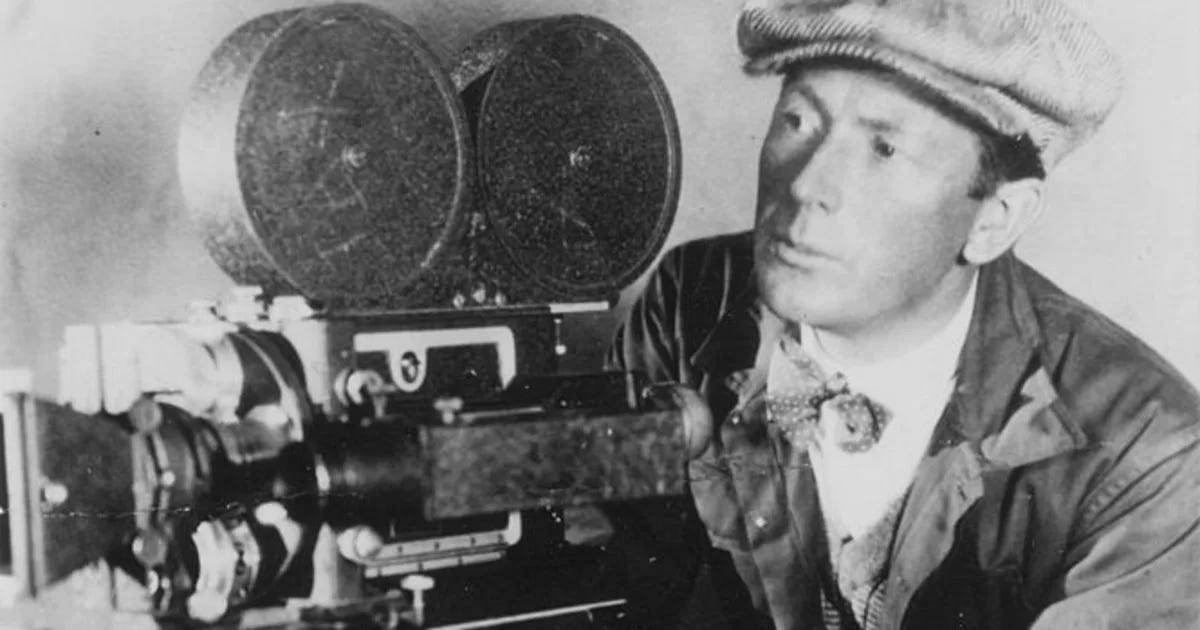

F.W. Murnau deserved more attention on the podcast. Time to do my penance.

If I have one regret about the first season of The Haunted Screen podcast, it’s that I didn’t dedicate more airtime to the life and work of F.W. Murnau. The director gets a sizable chunk of the second episode, where I look at how despite his personal aversion to antisemitism, the tropes of that particular strain of bigotry seeped into his 1922 vampire classic Nosferatu, and I touch on his ultimate fate in the finale. But where G.W. Pabst got an episode to himself and the power couple of Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou got two, Murnau always had to share space. The reasons for this have nothing to do his worthiness as a subject. His movies can go toe-to-toe with those of any Weimar filmmaker and his life story is compelling stuff: war, love, heartbreak, and a tragic early death, all played out against the backdrop of Jazz Age Berlin’s legendary queer scene. It’s just that I was building the THS plane while I was flying it, and by the time I realized I wanted to spend more time on Murnau, my fall semester had started in earnest. Teaching four classes across two different colleges doesn’t leave much bandwidth for research, writing, recording, and editing.

So over the next two weeks, I’ll be wrapping up some unfinished business and addressing a couple aspects of the Murnau story that I would’ve liked to include in the show. Today we’ll look at a masterpiece of his that I unconscionably ignored on the podcast, one that was, in part, a distinctly German response to the hyperinflation crisis. Then next week, we’ll place the director in the context of Weimar gay culture.

As I mentioned in last week’s post, I’ll be experimenting with format until the newsletter finds its footing. So in addition to some thoughts on Murnau, you’ll also get a mini-review of the micro-budget horror darling of the moment Skinamarink, and, by popular demand, a picture of Rotini in a snowman costume. (You’re welcome, Yvonne!)

Save The Last Laugh: Murnau’s Underseen Masterpiece

Nosferatu is unquestionably F.W. Murnau’s most famous film. Just mention its title, and even someone who doesn’t know Orlok from Orbach will be able to call to mind the grotesque and mesmerizing vampire at its center. And after trading Berlin for Hollywood in 1926, Murnau carved out a special place in American film history with the following year’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, which won the only Oscar ever conferred in the Best Unique and Artistic Picture category at the very first Academy Awards. Intended to honor the top art house film, the trophy was meant to stand on equal footing with Wings’ award for Outstanding Picture. While the Academy retroactively elevated Wings above Sunrise as the equivalent our contemporary Best Picture, it’s Sunrise that’s stood the test of time. Murnau’s movie came in at #11 on the latest Sight and Sound list of the all-time best. Of the 250 movies listed, Wings is not among them.

Even with those classics on his resume, there’s a case to be made that 1924’s The Last Laugh (German title: Der letze Mann, #234 on the S&S list) is the filmmaker’s most impressive achievement. Its story is simple, even archetypal. Our protagonist, played by Emil Jannings, is an unnamed doorman at a posh hotel. He is enormously proud of his job, and of the glimpse it offers him into the world of his social betters. His gold-braided uniform commands the respect of the residents of his working-class neighborhood. Age, however, comes for us all, no matter how fine our livery. Entering his dotage as the film begins, the doorman struggles to lift the luggage of the hotel guests, and he’s demoted to the role of bathroom attendant. Humiliated and stripped of his uniform, he becomes a source of shame for his family and an object of mockery for his neighbors. Just as all seems lost, fate intervenes. In a final, farcical twist, a millionaire dies in our hero’s arms. For reasons that are never made clear, said millionaire’s will stipulates that his fortune be left to the whoever tended to him in his last moments—none other than our ex-doorman. You could say that it’s he who gets the last laugh.

Part of the mission of The Haunted Screen is to explore how movies bear the mark of the time and place in which they’re made. In The Last Laugh, that mark is clear. The film was released just as Germany’s currency was stabilizing in the wake of the infamous Weimar hyperinflation crisis. Different sources give different numbers, but according to one account, a single US dollar—which had been worth eight German marks in 1918—was worth 4.2 trillion marks by the end of 1923.1 To formerly comfortable professionals whose social standing had collapsed amid the economic tumult, the doorman’s sudden ruin looked very familiar.

What’s more, the symbol of a Prussian-inflected uniform had a particular resonance in the highly militarized culture of the the recently-defunct German Empire. In the book that gave my little outfit its name, the critic Lotte Eisner writes of the film:

This is pre-eminently a German tragedy, and can only be understood in a country where uniform is King. A non-German will have trouble comprehending all its tragic implications.

Of course, Emil Jannings—the doorman himself—wasn’t immune to the allure of the uniform. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, he cozied up to Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and was all too happy to star in films that were effectively infomercials for fascist ideology. In 1924, though, that was all in the future, and Jannings’ doorman was unmistakably a man of the past. His bushy mutton chops were a relic of the Wilhelmine Era, fashionable during the reign of the Kaiser but embarrassingly out of step with the modern Weimar aesthetic. The times had passed him by. It was a moment when German society was changing rapidly. The monarchy had fallen, a tenuous new democracy rising in its place. Both communism and fascism were waiting in the wings, each hoping to lay claim to the future. In cities like Berlin, a new culture was emerging, with new art, new lifestyles, and new perspectives on class, gender, and sexuality. The old world was dying, and the new world was struggling to be born. For Germans of a certain age, the doorman's fall stood in for their own anxiety that their status and their worldview was slipping away.2

Even as The Last Laugh channeled social realities that were relevant to its audience, it wasn’t the plot that made the film a masterpiece. It was Murnau’s “unchained camera.” In the words of scholar Paul Cooke, the director and his cinematographer Karl Freund saw to it that “the camera itself became an actor in the film.” Check out a minute or two of the opening sequence for a case in point:

In an era before specially designed dollies allowed for smooth movement, Freund pulled off the glide through the hotel lobby by attaching the camera to a bicycle and personally riding it up to the revolving doors. And for a later scene where the doorman resorts to booze to drown his sorrows (37:30 in the video above), the cinematographer strapped the camera to his chest and stumbled about, bringing bringing the audience inside the character’s drunken mindset. At a time when most movies just let the action play out in front of a stationary camera, this was groundbreaking stuff.

More than any filmmaker of the Weimar pantheon, Murnau told his stories visually. His skillset was perfectly suited for the silent era, when the absence of dialogue meant that directors had no choice but to rely almost entirely on images to communicate with viewers. Few films, though, took this to the extreme that Murnau did in The Last Laugh, which was the apotheosis of his stated goal of stripping out “everything that isn’t the true domain of cinema.” This included title cards, that textual residue of novelistic storytelling. The movie’s entire 90 minute runtime includes just one intertitle, and that single exception was an expression of contempt for the movie’s weakest component: its sentimental coda, where the doorman’s fortunes are reversed by a ridiculous stroke of luck. When the protagonist is at his lowest, just before he happens into his millions, the solitary title card reads:

Here our story should really end, for in actual life the forlorn old man would have little to look forward to but death. The author took pity on him, however, and provided quite an improbable epilogue.

As Alyssa Katz noted at Criterion, the note suggests that Murnau is playing “the epilogue as belabored farce, a grotesque parody of a happy ending that can easily be mistaken for the real thing.” Some sources indicate that the ending was foisted on Murnau by Erich Pommer, producer of nearly every classic of the Weimar Era, from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to Metropolis to The Blue Angel. Pommer argued that American audiences hated sad endings, and he had designs on that huge, lucrative market. As usual, his commercial instincts were correct. The Last Laugh was a hit across the Atlantic, and its success cemented Murnau’s reputation and paved the way for his jump to Hollywood.

Mini-Review: Skinamarink

A slow, polarizing experimental horror film? As someone who loved divisive mother! and the glacially-paced Hagazussa, the buzz around this one couldn’t have been more up my alley. Kyle Edward Ball got his start with a YouTube channel called “Bitsized Nightmares,” where he turned fan-submitted bad dreams into Lynchian short films. In Skinamarink, he scaled up his operation but kept the sense of intimacy, shooting his feature debut in his childhood home in Edmonton on a budget of just $15,000.

If you’ve heard anything about it, you already know that this is a profoundly and self-consciously strange little movie. Inasmuch as there’s a plot, it’s this: It’s late at night, and two small children discover that they’re home alone. They set up camp in the den and put cartoons on the TV to soothe their nerves. Windows and doors disappear, furniture migrates to the ceiling, and an ominous voice urges them to come upstairs. As with Murnau’s work, though, Skinamarink isn’t about story. It’s about ambience—a slow building feeling of menace. The vast majority of Ball’s shots include no characters at all. You see toys in a darkened room. You see the corners where wall meets ceiling. Occasionally, you see the back of a someone’s head. It’s a quiet film with little dialogue—the kind of movie where you don’t want to chew your popcorn too loud for fear of ruining the moment.

It is, in other words, the worst possible movie to be seated, as I was, immediately next to a pair of loquacious assholes. People halfway down the row were turning to give the couple please-shut-up-and-stop-ruining-this looks, which they either didn’t notice or chose to ignore. After about half an hour, I—someone who will go to significant lengths to avoid confrontation—gathered my courage and asked them to keep it down. It worked. Sort of. So my viewing experience of Skinamarink was less than ideal. I wasn’t fully able to slide onto its wavelength, and it’s not 100% clear to me how much of that was due to the movie itself and how much was due to the couple on my right.

Despite the genuinely creepy tone and unsettling atmospherics, it wasn’t exactly scary. It veered in that direction a few times—a woman facing away from the camera speaks to her child in a flat monotone, a flash image of a girl whose mouth has been rubbed out—but there was no feeling of momentum or acceleration. The images didn’t build on one another so much as sustain the same slow sense of low-level discomfort. The succession of shots of LEGOs on the ceiling or analog distortion on the TV screen could’ve continued for twice as long or been cut in half and the effect would’ve been more or less the same. No arc. No climax.

All that said, Skinamarink is, I think, still a movie worth seeing. It’s an attempt at a new approach horror, and one produced on a shoestring budget. Watching someone stumble toward an original vision is always more interesting than watching them competently pull off something formulaic. Whatever Ball tries next, I’ll be there for it.

Odds & Ends

Miss my essay in LitHub last week?

Then here I am discussing the origins of my Weimar obsession and finding some unsettling parallels with the present.Haven’t listened to the pod yet?

You can find it on Apple, Spotify, Google, or pretty much any other platform.What about social media?

Twitter and Instagram are the best bets. There’s a Facebook page, too, but I’m not especially diligent over there.

Funny how the generational conflicts of the 1920s mirror those of the 2020s, isn’t it? I mean, not funny ha-ha, but funny… terrifying?