Weimar Queer Culture, On- and Off-Screen

Plus: The long overdue release of a dissident filmmaker.

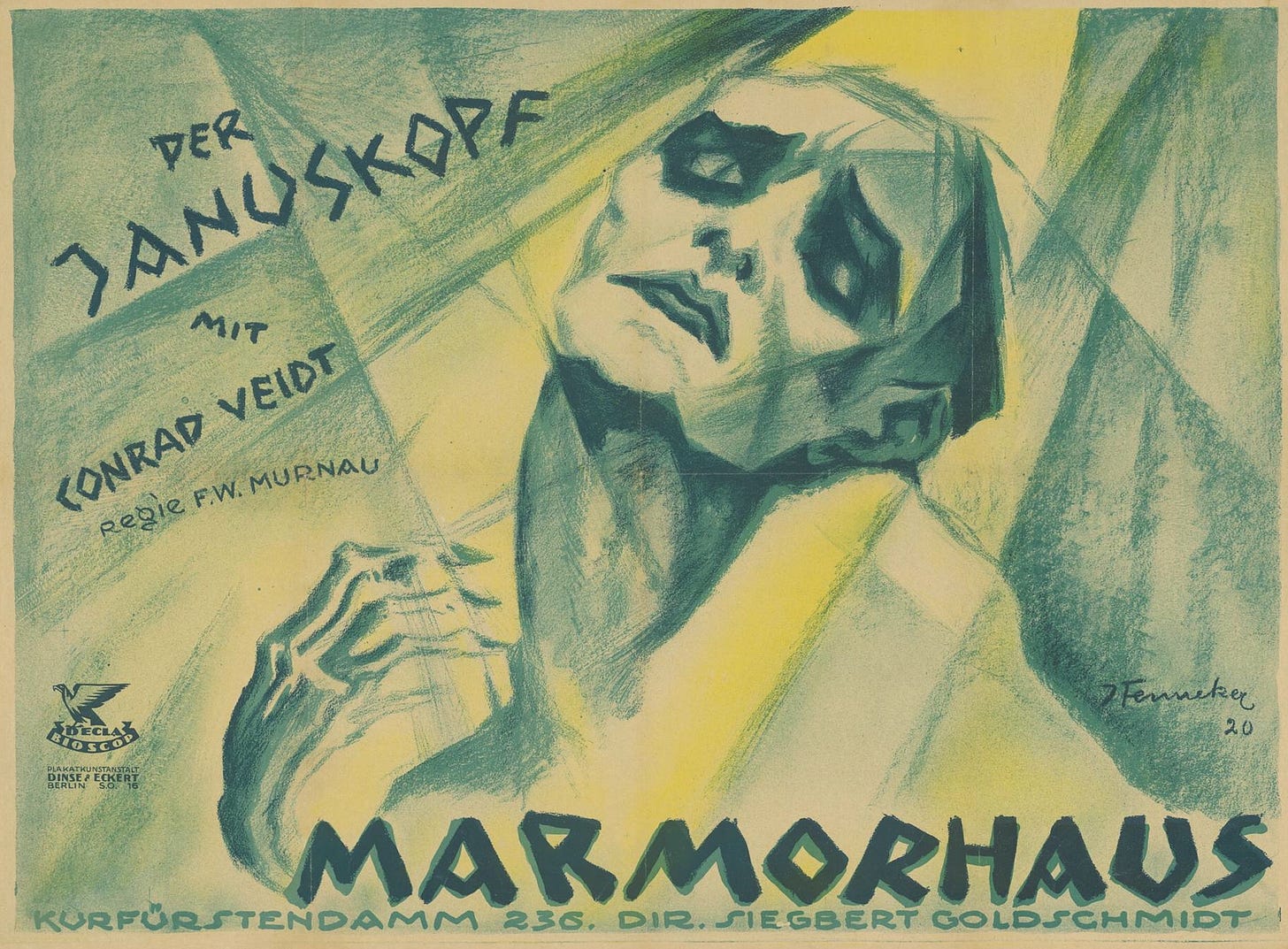

It’s hard to fathom how little we actually know about the first years of international cinema. The Deutsche Kinemathek archive estimates that somewhere between 80 and 90% of all silent films are lost. The nitrate film used for prints and negatives until the 1950s was both brittle and highly flammable, and the preservation of this nascent art form just wasn’t a priority, so today we’re left with only a small fraction of the era’s cinematic output. One of those lost films is 1920’s Der Januskopf, a retelling of the Jekyll and Hyde story from Nosferatu director F.W. Murnau. In the excellent docuseries Queer for Fear, the scholar Harry M. Benshoff observes that this choice of material suggests the filmmaker was attracted to “themes of doubled selves, a self that is presented to the world and a self that is secret and hidden, that is the more libidinal, eroticized self.” Murnau was gay, and while it’s of course impossible to know whether and how this facet of his identity surfaced in Der Januskopf, the connection Benshoff is drawing makes intuitive sense.

Like the film, most of the details of Murnau’s romantic life are lost to history. I cover much of what is known on the second episode of The Haunted Screen podcast, namely his youthful affair with the budding poet Hans Ehrenbaum-Degele. Like millions of men of his generation, Hans died in the meat grinder that was World War I, and sources paint a contradictory picture of Murnau’s relationship with his sexuality after this heartbreak. Some claim he was openly gay and others insist he was closeted. Whatever the case, though, there’s little doubt that he would’ve been aware of the legendary queer scene emerging around him in 1920s Berlin.

I’m using the first few editions of this newsletter to tie up some loose ends from the podcast, and this is a strand of Weimar culture that I didn’t adequately explore on the show. Last week, we looked at an underseen Murnau classic that offers insight into his era’s economic turmoil, and this time around, we’ll touch on Berlin’s LGBTQ+ community. Of course, I’m only going to scratch the surface here. From expat writer Christopher Isherwood, whose autobiographical fiction would inspire the musical Cabaret, to scholar Robert Beachy and his acclaimed history Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity, this ground has been covered by people who know a lot more about it than I do. But hopefully my little primer can fill in some blanks from the podcast and point you in the direction of sources that go deeper.

Even before the Kaiser abdicated and the Weimar era began, Berlin had established a reputation as the queer capital of Europe. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, it was a military town, and in such a heavily male environment, soldiers frequently turned to each other and to the teenage sex workers known as line boys. Formally, Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code had banned “unnatural fornication […] between members of the male sex” since 1871. As far back as the 1880s, however, Berlin Police Commissioner Leopold von Meerscheidt-Hullessem realized that it enforcing a law against a private act was futile. Rather than arrest suspected gay men, he chose, in Beachy’s words, to “keep tabs” on them, allowing gay bars and even “transvestite balls”1 to operate without state interference.

In this atmosphere of official toleration, clubs like the Eldorado flourished, attracting a clientele broad enough to include both Marlene Dietrich and Nazi leader Ernst Röhm. Queer publications like Der Eigene (The Unique), founded in 1896, circulated freely. Several strains of gay politics emerged, sometimes in direct opposition to one another. According to Mel Gordon, author of Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin, the right-wing “Militant Homosexualists” merged a gay male supremacist ideology, an admiration for Ancient Greek pederasty, and a fixation on fascistic racial purity, while the left-leaning “Third Sexers” argued that gay men occupied a space between male and female sexualities and that all consensual adult sex was equally legitimate.

At the forefront of the latter camp was the physician Magnus Hirschfeld. Distraught at the suicide rate of his gay patients, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in 1897 to advocate for the rights of queer Germans. It’s generally regarded as the first LGBTQ+ advocacy group in history. His other organization, the Institute for Sex Research—a forerunner to the famous Kinsey Institute—conducted serious, nonjudgmental research on human sexual behavior and even pioneered early forms of gender-affirming surgery. He was in many ways far ahead of his time, though his legacy is complicated by his inability to see past his society’s racism and misogyny.

In 1919, Hirschfeld’s Institute financed a film he co-wrote called Different from the Others. Intended to agitate for the repeal of Paragraph 175, it stars Conrad Veidt—Cesare from The Cabinet of Caligari Dr. Caligari—as a gay violinist blackmailed for his sexuality. Never one to shy away from the spotlight, Hirschfeld shows his acting chops in the role of a doctor who testifies on Veidt’s behalf. Even in the relatively permissive atmosphere of Weimar Berlin, this kind of work wasn’t without risks. Himself both gay and Jewish, Hirschfeld was attacked by proto-fascist street thugs in 1920 and beaten so badly that police on the scene initially declared him dead. He wasn’t. Hirschfeld would continue his crusade against homophobia until he died in exile in 1935.

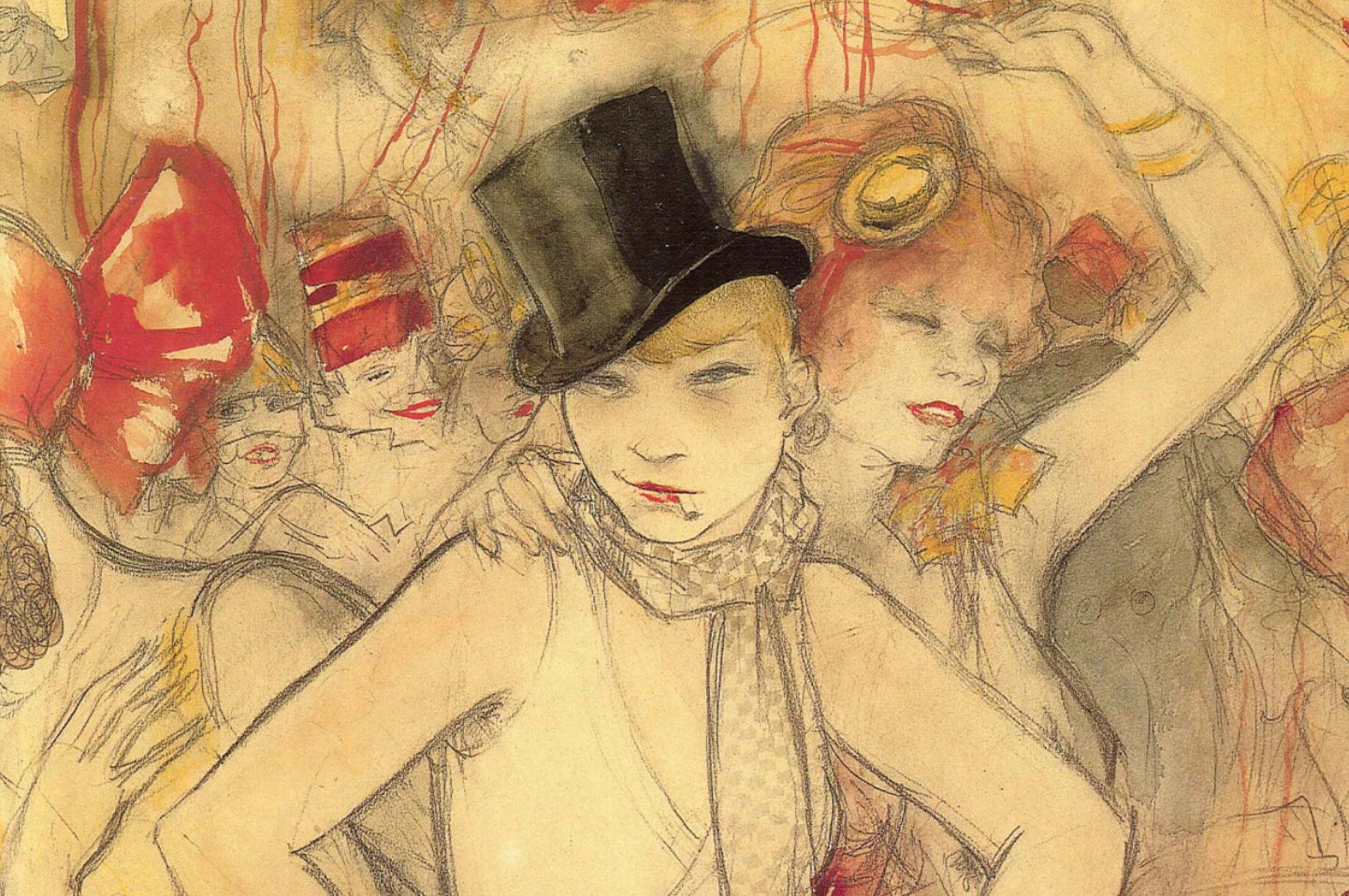

Though less well-documented than the men’s scene, a lesbian subculture also flourished in Weimar Berlin. Gay women frequented many of the same bars as their male counterparts and organized their own social clubs with names like the Whistle Club and Ladies Club Erato. The largest of these, the Club Monbijou of the West, boasted around 600 members who were known for their chic French menswear and shaved eyebrows.

Two of the era's most important queer icons were also two of its biggest movie stars: Marlene Dietrich and Louise Brooks.2 While Dietrich was married to film industry insider Rudolf Sieber for more than half a century, their relationship was an open one and she carried on numerous affairs with men and women alike. Even after moving to the United States in 1930, Dietrich retained much of her androgynous Weimar aesthetic both on-screen and off. Portraying a nightclub singer in Morocco, for example, she famously donned a tuxedo and top hat and kissed a woman in the audience, scandalizing conservative American audiences.

Brooks, a Kansas-born expat, didn’t identify as gay or bisexual, but she made no attempt to hide her close social ties to lesbian circles in Berlin and Los Angeles or her occasional liaisons with women, including fellow megastar Greta Garbo. As one biographer put it, “The operative rule with Louise was neither heterosexuality, homosexuality, or bisexuality. It was just sexuality.” This openness translated on-screen, too, most famously in G.W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box, where a wealthy countess falls for Brooks’ Lulu.

Of course, the golden age of Weimar queer culture collapsed when the Nazis took power in 1933. Gay clubs and publications were shuttered. The library of Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sex Research was raided and its books burned. An estimated 100,000 Germans were arrested on charges of homosexuality during the Third Reich, and 10-15,000 were sent to concentration camps. Tragically, the repression didn’t end with the defeat of Nazis. Queer survivors of the Holocaust were not officially recognized as victims, and were therefore ineligible for reparations. Paragraph 175 stayed on the books for decades. In West Germany, another 50,000 gay men would be convicted before its partial repeal in 1969. Homophobia may thrive under totalitarianism, but you just have to look at the current groomer panic to see that that it can exist quite comfortably in a liberal democracy, as well.

Some Good News: Iranian Filmmaker Jafar Panahi Out on Bail

After seven months in Tehran’s Evin prison, Jafar Panahi was released on bail last week. The Iranian government was seeking to reactivate his six-year sentence for “propaganda against the system,” a charge stemming from Panahi’s connections to the 2009 protest movement that followed a disputed presidential election. The release, which authorities insist is temporary, came two days after the filmmaker began a hungry strike. “I will refuse to eat and drink any food and medicine until the time of my release,” he’d said in a statement. “I will remain in this state until perhaps my lifeless body is freed from prison.”

Panahi’s resume reads like a laundry list of the highest honors in film: Berlin’s Golden Bear, Cannes’ Camera d’Or, a Golden Lion and Special Jury Prize from Venice. A few weeks ago, I saw his latest project No Bears at Manhattan’s Film Forum. For years, Panahi has been banned from making movies or leaving the country, so the unauthorized No Bears was smuggled out of Iran on a thumb drive hidden inside a cake. Panahi plays himself, confined to Iran but using wifi to furtively direct a film across the border in Turkey. It’s a fascinating movie, critical not only of Iranian authorities, but of a patriarchal culture, of restrictive national boundaries, and of the medium of film itself. If it’s playing near you, it’s well worth a watch. And if it’s not, make a note to see it when it comes out on streaming.

Odds & Ends

Need to catch up on the podcast?

You can find it on Apple, Spotify, Google, or pretty much any other platform.What about social media?

Twitter and Instagram are the best bets. There’s a Facebook page, too, but I’m not especially diligent over there.

It’s difficult to apply our 21st-century gender categories to the Weimar era. The term “transvestite” (Transvestit in German) was most commonly employed at the time and is preferred by scholars like Beachy, which is why I use it here. This outdated category, however, elides important contemporary distinctions. We can’t, for example, be sure whether the individuals in the Eldorado photo would today identify as trans women or as men in drag.

Brooks’ life story is discussed at some length in the fourth episode of the podcast and Dietrich is a major focus of the season finale.